Most artifacts recovered from a site are easy to identify. Broken ceramics that were once part of a serving dish or tea cup, shards of olive-colored glass that were parts of a wine bottle, nails that held down the floorboards of a house that has vanished from the landscape. These artifacts are ubiquitous on historical archaeological sites, but they’re also objects that we live with today, and that most people can easily recognize.

Then there are the things that give even the most seasoned archaeologists a run for their money. Artifacts that represent just one component of a larger, more complicated object, and when taken out of that context, are difficult or even impossible to identify. Like this thing, recovered by volunteers from the southwest corner of the Eutaw cellar last spring:

When we found it, we assumed this small, brass object was associated with a door or window lock, since it was found with several other pieces of window and door hardware. On its own, this object seems both inscrutable and unimpressive, but it once served an important function, both as a quotidian bit of household hardware, and as a reminder of the complex social and interpersonal dynamics at that touched the lives of all the residents of Eutaw Farm’s main house.

If you watched Downton Abbey, you may recall the bells hanging on the wall in the servant’s hall, “downstairs”.

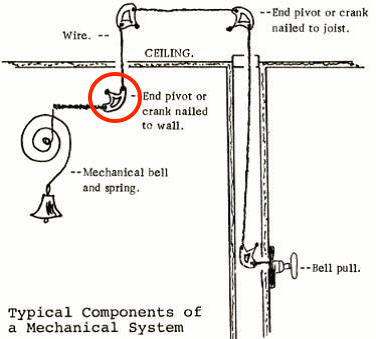

House bells, also known as servant’s bells, were first introduced into the homes of wealthy families in the early eighteenth century, but grew in popularity through the early twentieth century. The house bell was a system that allowed the residents in the living quarters to summon servants or enslaved persons in the lower, hidden portions of the house. This occurred via a network of wires and pulleys that were likewise hidden, only the bell pulls and the bells themselves visible, arranged in such a way that the person being summoned would know immediately who was ringing the bell, and where.

Before these contraptions were introduced, servants, whether free or enslaved, were summoned by handbells, or by someone simply yelling for them (Murtha 2010). With the invention of the house bell, summoning someone from the kitchen, cellar, or their own sleeping quarters required only the tug of a cord or press a button.

House bells could be installed in any – or every – room of the house. At houses like Eutaw, house bells were installed in bedrooms, the dining room, the drawing room, and the parlor – anywhere the (white) family spent significant amounts of time and might require food to be brought from the kitchen, beverages to be provided, bedpans to be emptied, laundry to be delivered and collected, children to be tended, etc., etc.

Recent scholarship from the University of Virginia’s excavations at Poplar Forest and by John Crowley (2003) and Wendy Danielle Madill (2013) suggest that the house bell served as a convenient innovation for white enslavers (the Hall family), and a means of further domination over the enslaved (the family of Emeline Jones and Henrietta Gittings).

The separation of space offered by the house bell system was most beneficial – obviously – to the white families who installed them. The practice of slavery was considered a luxury, a sign of gentility and economic success. At the same time, the constant presence of an enslaved person was viewed by some as a hindrance to their personal privacy. Thomas Jefferson certainly felt this way; he ordered the installation of the bell system at Poplar Forest expressly for this reason. He could call for the workers he enslaved when he wanted them, but could otherwise be left to his own pursuits or hold “a free and unrestricted flow of conversation” with a friend without reserve (Hunt 1906). The installation of the house bell system at Eutaw suggests that the Hall family likewise wished to escape the “constrictions” inherent in the presence of the people they held in bondage.

So house bells were positively liberating for the people on the bell pull end, but what about the people who had to respond to the constant ringing?

House bells allowed for greater physical distance between enslaver and enslaved, which might seem mutually beneficial. But the device also promised greater control over the regimentation of the lives of enslaved people. As Wendy Danielle Madill (2013) wrote on the topic:

“…bell systems stratified master and servant [slave] space while increasing a sense of privacy for both groups. However, this privacy did not increase servant [slave] freedom; instead, the very act of noiseless summons increased masters’ control and convenience. This controlled regimentation of servant behavior played into a desire for a refined lifestyle where servants [slaves] noiselessly obeyed the commands of their superiors. Though they did not have to stand at attention in thresholds waiting for a vocal command, servants [slaves] were compelled to instantly obey their masters’ summons and behave like puppets on a string—dropping their personal duties to answer a bell at a moment’s notice.”

This is one perspective; another is that the house bell provided more privacy for the “masters,” by keeping those they enslaved out of spaces reserved for white families and their visitors, at the expense of the privacy of the enslaved. The house bell is a physical manifestation of the white enslaver inside a primarily black, enslaved space. While slaveholders always had full access to the quarters, and could enter at any time, with a house bell, they took up full-time residence, albeit remotely.

Our previous historical research and excavations at Eutaw have revealed the names and stories of several dozen people enslaved at Eutaw, including Emeline Jones and her mother, Henrietta Gittings, both of whom resided in the northeastern wing of the house. This single artifact tells us a story of the costs and benefits of technology, and the ways in which inequality manifested within the household. It hints at what the busy household might have sounded like, at least for Henrietta Gittings, Emeline Jones, and the other enslaved and free African American people who resided there. And it makes us wonder how each of the individuals affected by this new technology felt about it, as wires and pulleys, like the one we found last spring, were being secreted behind the elegantly plastered walls of Eutaw’s big house.

References

Crowley, John E.

2003. The Invention of Comfort: Sensibilities and Design in Early Modern Britain and Early America. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Gerhardt, Tom H.

1979 “Old House Intercoms: Buzzers, Beepers, Buttons, and Bells.” Old-House Journal,

October 1979.

Madill, Wendy Danielle

2013 Noiseless, Automatic Service: The History of Domestic Servant Call Bell Systems in Charleston, South Carolina, 1740-1900. Master’s Thesis, The Graduate School of Clemson University and College of Charleston.

Murtha, Hillary

2010 “Instruments of Power: Sonic Signaling Devices and American Labor Management, 1821–1876”. Ph.D. dissertation submitted to University of Delaware.

So interesting. My great-grandfather, Parkin Scott Kerr, ran the cotton mill located in the Jones Falls and Druid Hill Park area. Although the family weren’t wealthy and didn’t have servants, I still love to learn about all things Baltimore.

LikeLike

Oh, how cool that you have a family connection to Baltimore’s history as the cotton duck capital of the U.S.! We love learning all about Baltimore, too. Thanks for stopping by and reading!

LikeLike

You’re welcome. I’m looking forward to your posts.

LikeLike

Hi! Your post was featured as our #artifactoftheday on American Artifacts Blog. See it live here: https://americanartifactsblog.com/house-bell-baltimore-md/

LikeLike

Cool! Thank you so much!

LikeLike

We would also like to inform you that we also featured another set of servant bells from Popular Forest Plantation. See post here: https://americanartifactsblog.com/servant-bell-system-3d-popular-forest-plantation-va/

LikeLike

Oooh, neat! I believe we saw more components of the house bell system as we were cleaning artifacts in the lab last week. We’ll have to see how this system compares to TJ’s. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person