As coincidence would have it, the same time William Smith was positioning himself as one of the more prominent merchants of Baltimore, tensions between Great Britain and her American colonies were steadily growing. Maryland’s reaction to the increasingly stringent British policies of the 1760s and early 1770s was more restrained than neighboring colonies, due largely to the colony’s protracted bickering between popular and proprietary forces such as the continual border dispute with her northern neighbor, Pennsylvania. As such, little time was left over to worry about imperial politics. However, despite Maryland’s various distractions, there were several instances where some prominent Marylanders began to publicly express their growing frustration with Great Britain and their treatment of the colonies in the years following the French and Indian War.

Maryland lawyer Daniel Dulany’s pamphlet opposing the Stamp Act in 1765 drew significant support for the patriot cause, as did resolutions passed by the assembly and articles published in the Maryland Gazette (Schultz 2009). By the early 1770s many Marylanders reacted strongly to the Tea Act Crisis and resulting Boston Port Bill. Anthony Stewart, a ship owner, brought the tea-laden Peggy Stewart into Annapolis harbor for the purpose of selling the tax-paid product. When Anthony Stewart, paid the tea tax, he violated the non-importation resolution implemented by the protesting Maryland colonists. A crowd had gathered in Annapolis threatening Stewart’s life if he did not destroy the ship and its cargo. Fearing for his own life and that of his family in town, Stewart sailed the ship into full view of the city and set it afire. None of the 2,300 pounds of tea reached shore.

Like many who joined the patriot cause, William Smith’s motivation were likely complex and nuanced. In fact, it is somewhat surprising to find Smith on the side of the patriot cause given his position as the owner of a prominent shipping enterprise. Trade was the central issue for many of Maryland politicians and citizens as they navigated the increasingly tense colonial crisis of the 1760s and early 1770s. Many of Maryland’s thriving merchants bristled at the implementation of the American non-importation resolution and often found themselves on the side of the Loyalists (Schultz 2009). Wealthy merchants, like many of Smith’s contemporaries, tended to remain loyal to the crown, at least initially, as they feared independence for Great Britain would mean the loss of economic benefits derived from membership in the British mercantile system. While the various taxes and tariffs imposed by Great Britain were seen as an inconvenience, many merchants often passed those added costs onto their customers.

Perhaps Smith found his interests more in line with the Patriot cause given the very nature of his enterprise. Unlike those merchants specialized in importing goods into the colonies, the primary profits from Smith’s commercial enterprise relied on the exportation of wheat and other products out of the colonies to Europe. Smith business and that of his fellow merchants in the American colonies were restricted in by a series of British laws enacted during the mid-seventeenth century called the Navigation Acts. The series of laws essentially restricted how and who American merchants sell their goods between the colonies and Europe. For William Smith, the Navigation Acts required him to ship all his exports to Great Britain for resale by English merchants no matter what price he could have obtained elsewhere. While Smith’s wheat exports were often less restricted than other colonial products such as tobacco and molasses, the Navigation Acts were likely seen as an injustice by the Baltimore merchant. By siding with the Patriot cause, Smith likely saw the possible separation from Great Britain as a means to open the American markets, and his own business enterprise, to the rest of the world without Britain serving as a middleman.

Whether his motivations were based on financial reasons or tied to more lofty ideals of liberty and home rule, by 1774 William Smith joined the Patriot cause. That year, William Smith was appointed a member of Maryland’s Committee of Correspondence along with several other prominent Marylanders including Charles Carroll, William Paca, and Samuel Chase. Committees of Correspondence served as a vast network of communication throughout the American colonies between Patriot leaders. They were often groups appointed by the colonial legislatures to provide leadership and aid inter-colonial cooperation. The committees played a major role in promoting colonial unity and by September 1774, organizing the First Continental Congress, a majority of whose delegates were committee members. Smith was not a member of the Maryland delegation that attended the First Continental Congress, but continued his efforts for the Patriot case from home as a member of the Baltimore Committee of Observation. This committee, also known as Committees of Safety, were composed of Patriot members who together took it upon themselves to enforce the boycott of British goods and other policies enacted by the Continental Congress. Eventually these committees became the defacto colonial governments in the colonies and the former royal governments were dismantled over the course of the American Revolution. Another role assumed by the Committees of Observation and Safety was that of court and jury, often imprisoning, deporting, or otherwise “dissuading” those with Loyalist leaning from supporting British rule.

On February 15, 1777, William Smith was elected as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress which at that time was currently in its second session at the Henry Fite House in Baltimore. Smith would only serve as a delegate for 12 days until the end of the session on February 27, 1777 (Bevan 1947). During his first role as statesmen, Smith principally concerned himself with issue of the navy and clearing the waterways of the Chesapeake and Pennsylvania.

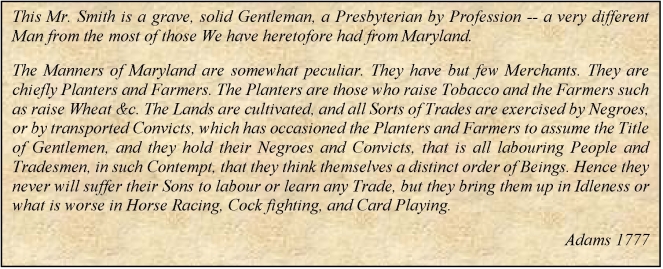

In fact, the very subject was the primary topic of interest when William Smith invited John Adams to dine at his home in Baltimore on February 23, 1777. According to Adams’ accounting of the occasion in his personal diary:

Of particular interest in the diary; however, was not the dinner conversation but Adams’ personal account of Smith the merchant as well as the various planter gentlemen that he has become accustom:

Given William Smith’s concerns for trade and the navy during his short time with the Continental Congress, it appears he influenced some members of the delegation to elect him as a member of the committee for the Navy Board in the Middle District. The Navy Board was established under Congress’ Marine Committee whose charge was to establish a continental navy. The Navy Board, established on November 6, 1776, consisted of a three-person panel directed to execute the business of the navy for the Marine Committee. The first to be appointed were John Nixon and John Wharton of Pennsylvania and Francis Hopkinson of New Jersey. On May 9, 1778, John Nixon resigned from the Navy Board and Congress elected William Smith to take his place (LOC 1912). The same day, Congress also approved that $20,000 be advanced to the Marine Committee for the use of the Navy Board. The fund served a variety of purposes including the outfitting of new or repurposed naval vessels and the evaluation and disposing of prizes taken by continental cruisers. Smith’s tenure with the Navy Board was short lived. In a letter dated July 17, 1778, Smith informed Congress that “his private business puts it out of his power to give any further attendance at the navy board now removed to Philadelphia and therefore requests Congress will accept his resignation” (LOC 1912). On July 22, 1778, Smith’s letter was read in chamber and his resignation accepted. Following his term on the Navy Board, William Smith returned to the life of a private citizen. While he occasionally provided various provisioning services to Congress and the Continental Army at various times during the Revolution, William Smith’s role as public servant was at an end, at least until after the war’s conclusion.

Previous: William Smith: 1728-1761 Next: William Smith: 1779-1804

References

Adams, John

1777 The Diary of John Adams No 28. Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts. Accessed online at https://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/archive/index

Bevan, Edith Rossiter

1947 The Continental Congress in Baltimore, Dec. 20, 1776 to February 27, 1777. In Maryland Historical Magazine Vol. 42. On file at the Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, Maryland.

Library of Congress [LOC]

1912 Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774 – 1789. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Schultz, Emily L.

2009 Maryland in the American Revolution. An Exhibit by the Society of the Cincinnati. Anderson House, Washington, D.C. February 27 – September 5, 2009.